Strike action, in the context of collective bargaining, does not belong in post-secondary institutions.

This has never been more evident than now, as unionized college teachers across the province will be legally allowed to strike as early as the week after Thanksgiving, if they cannot reach a new collective agreement with the College Employers Council.

Strike action by faculty in colleges directly results in a financial penalty of thousands of dollars’ worth of lost class time, on an institutional scale.

That’s thousands of dollars, in both public funds and tuition money, being flushed down the toilet every time the union representing college teachers fails to negotiate successfully.

When services like ambulance, police and the Toronto Transit Commission wish to strike they must negotiate an “essential services agreement” so their service will not be interrupted, according to the Crown Employees Collective Bargaining Act.

Why is education not given the same status as a public service?

Colleges in Ontario are publicly funded. While this money may not be funding a traditional service, it represents an investment in economic growth. The government is investing in educating students, to create new jobs and future prosperity. If that investment stopped, there would be immediate economic repercussions.

This may not have been the case when Algonquin opened 50 years ago, but in celebrating half a century and record high enrollment numbers, it’s time we also change how we view the public service that is education.

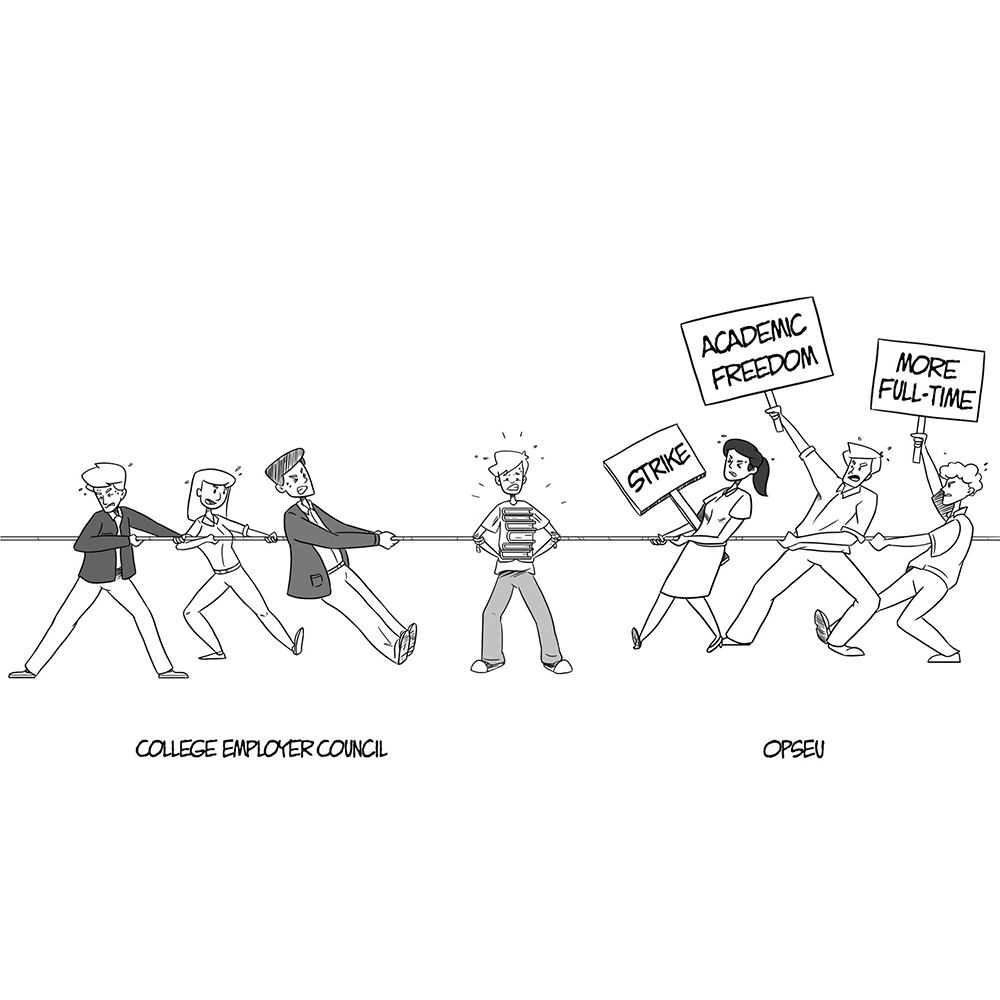

The teachers’ union has reported that their two main points of contention are to do with academic freedom and the ratio of part-time to full-time teachers. In layman’s terms, the union wants more full-time positions in colleges as well as more control over the curriculum via establishing teachers’ senates within individual colleges.

As reported previously by the Times, teacher senates are considered an administrative issue, not a term of employment. Which means they can’t be negotiated as part of a new collective agreement.

The union, on the other hand, has reported that the main reason they’re moving forward with strike action is because the colleges are unwilling to negotiate meaningfully.

Now, consider the fact that the last time college teachers went on strike in 2006, one of the main points being negotiated was exactly the same.

There is very obviously something wrong with the bargaining process, if nothing has changed in the last 10 years and if the main issue is a lack of understanding between two parties on what they’re even negotiating.

Students shouldn’t be forced to take sides in an argument that has nothing to do with us. We shouldn’t have to worry about union politics, college administrative issues or whether to study for a test that might not happen if the college is closed on Monday.

In 2006, the strike lasted for 18 days and did not end in a productive agreement, rather in arbitration. It’s true that the union represents about 12,000 faculty across the province, but a strike will affect more than 150,000 students.

Looking at these facts, it’s difficult to narrow down exactly what the union thinks they can achieve with a strike, or why they hold the legal right to strike at all.

The only thing that’s certain is that students will be left high and dry. We are the helpless, innocent bystanders in a fight between our government and our teachers; two parties that are supposed to exist for our benefit.