The hardest lessons learned are the ones that stick.

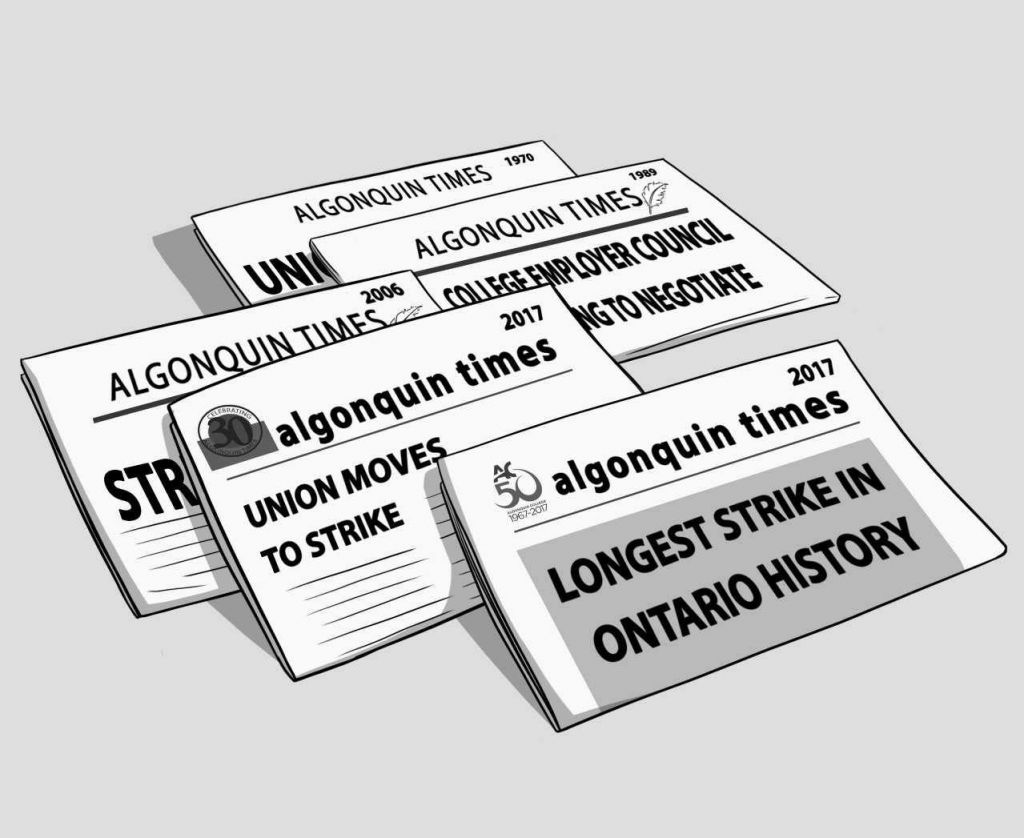

If there ever was an example of how true that is, look no further than the many lessons imparted during the Ontario college strike of 2017.

We learned that students want to be included in the discussion if people would listen.

We learned that colleges had absolutely no plan for the inevitable work stoppage.

And we learned that faculty are willing to hold our education hostage as a bargaining chip.

This, of course, wasn’t the only such lesson we have had before – there were three previous strikes in 1984, 1989 and 2006, all with their own takeaways. But each and every time, we’ve ignored clear messages and allowed the next generation of students to suffer for the labour dispute of the day.

Collective bargaining didn’t work this year. It didn’t work in 2006. It has never worked in the college sector.

So, the question we should all be asking as we walk away from this 36-day strike is: How can we ensure another strike in 10 years doesn’t last twice as long?

As the archives of the Algonquin Times show, there are very few differences between this and previous strikes. The colleges were always unprepared. The students had the same concerns. Even the issues are often comparable.

For decades, colleges and academic employees have been unable to have productive negotiations. Bargaining has always been painful, protracted and ineffective at resolving differences between employer and employees to a troubling degree not commonly seen in any other sector.

Jeffrey Gandz put it best in his 1988 report to the government on the system’s state of collective bargaining: “dysfunctional” was the word he used to describe the relationship between faculty and colleges.

If the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result then, folks, we’re batty.

It should be obvious now that the future of students cannot be placed in the care of two parties who, since the very first collective agreement was inked in 1971, have shown an inability to work together for the public’s benefit.

Collective bargaining in the college sector has failed time and time again. It is time to abolish it and declare colleges an essential service.

The Algonquin Times said as much in an editorial preceding the strike. But in the shadow of the longest strike in history, it’s worth repeating.

Now it’s time for action.

During the strike, students and student associations showed an incredible tenacity to mobilize and be heard. Now that classes are back on, many will feel their role is finished.

It isn’t.

Students must maintain their momentum and push to end strikes in colleges forever. Never again should a college student go weeks in fear that their thousands of tuition dollars were wasted.

The government should repeal the Colleges Collective Bargaining Act and bring unionized college employees under the Crown Employees Collective Bargaining Act, which will ensure that students’ education is not unduly interrupted in the event of job action.

This isn’t a new idea. In fact, college employees were not even allowed to strike until 1975.

From 1967, when the system was created, to 1975 employees were considered civil servants and fell under the purview of crown bargaining laws. Rather than allowing for a strike or lock-out, these laws sent unresolvable issues to binding arbitration.

Arbitration is a legal process where a neutral third party hears from both sides and then renders a final decision that cannot be appealed.

It’s been used consistently in the college sector. The very first collective agreement in 1971 had to be settled under arbitration after the two parties couldn’t even agree on which employees the union should represent.

In fact, every previous strike — 1984, 1989 and 2006 — have been settled through the involvement of binding arbitration.

It will continue to be the sole way issues are addressed, now that the unresolved disputes of this year’s strike have also been sent to arbitration.

Now, wouldn’t it be so much better if we did that in the first place instead of going through a five-week strike?

History doesn’t have to repeat itself.