The phone does not stop ringing at the Distress Centre of Ottawa and Region. That’s where suicide hotline operators answer nearly 50,000 calls every year.

They even take calls at 3 a.m. on Christmas Day – because, of course, suicidal feelings – a symptom of many mental illnesses – do not take holidays off, and sometimes, they work the night shift. In fact, mental illnesses don’t run on any concrete schedule whatsoever.

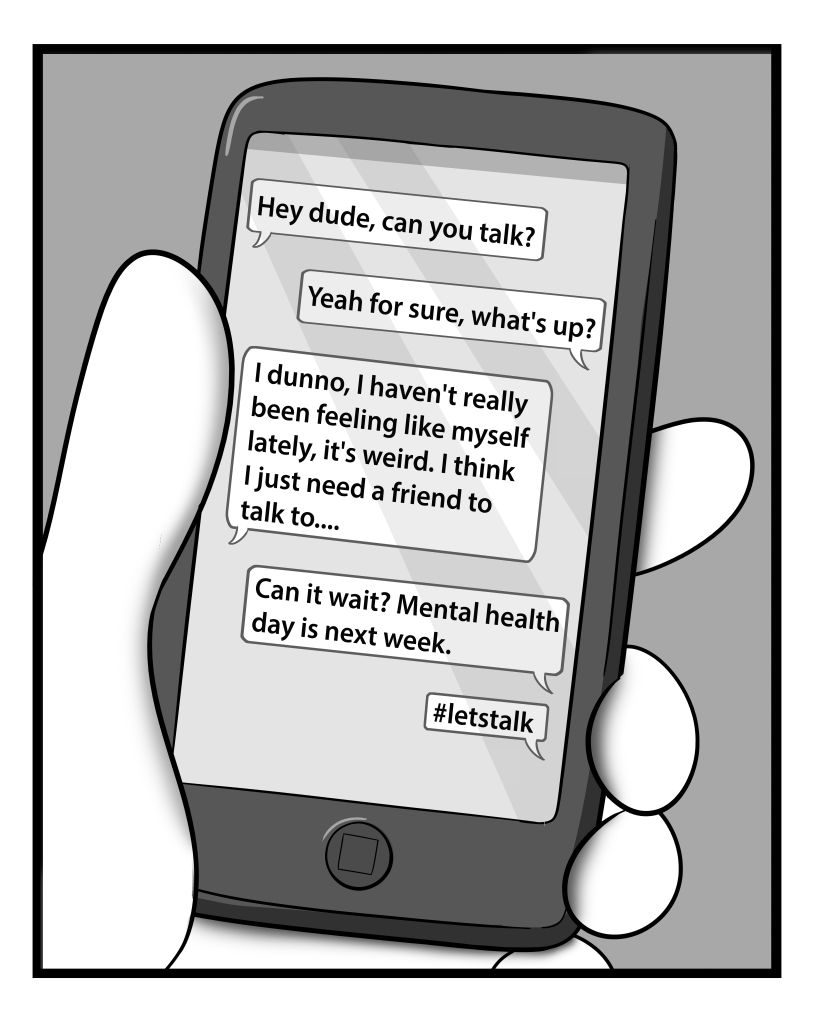

So, why do we, as a society, treat mental illnesses as if they can run on our schedule?

When we talk about mental health, we often do so in a counter-productive way that lies at the expense of those suffering. To effectively deal with the issues brought on by mental illness, we need to change when we talk about it and what we say.

Not surprisingly, ‘#BellLetsTalk’ became a massive trending topic on Twitter on Jan. 27, as many used the annual platform to share their own experiences and advice. Big names like Ellen DeGeneres and Justin Bieber tweeted their support of the movement. For a day, it became cool to talk about mental health.

It also raised more than $6 million within a 24-hour period. With the movement’s name in mind, people began to talk. Many felt comfortable enough to share their personal struggles with mental illness.

After it ended, these stories were being shared far less. Mental health was just as important of an issue the days before and after Jan. 27, although Twitter’s trending topics list did not reflect that. The drop in discussions happened because mental illness was no longer a central topic of discussion, and as a result, many felt less inclined to share.

But if we treat Bell Let’s Talk day as a springboard for discussion, rather than a limited period in which talking is effective, more can be accomplished. After all, the stories that were shared on Twitter on Bell Let’s Talk day are just as valuable without their attached five-cent donation as they are with the donation. Bell has created an opportunity to share about mental health with effectiveness. Other organizations that have the same reach that Bell has should carry the torch and keep the dialogue open.

If we truly want to improve the way we talk about mental health, then let’s keep the dialogue open even when there’s no event, no buzzword, and no hashtag.

Consider the tragedy of beloved actor Robin Williams, who committed suicide on Aug. 11, 2014. When news of his suicide broke, a public outcry occurred – the devastated public shared their condolences, and suddenly, depression became a major news topic, inspiring plenty of articles, op-eds, and social media discussions. Writer Dean Burnett wrote a powerful piece for the Guardian, in which he urged to readers that Williams’ suicide was not a selfish act. Burnett’s plea was thoughtful and well-written, and excellently served as a reminder that depression is a legitimate disease that should not be overlooked or discredited.

Even if articles like Burnett’s would be necessary and useful even if Williams hadn’t committed suicide.

Many struggle with depression every day—in fact, the Canadian Mental Health Association says that eight per cent of Canadian adults will experience a phase of major depression in their lifetime. At any given moment, many people are struggling with mental illness, so any time would be appropriate to talk about the seriousness of it. We don’t need to wait until mental health becomes a trending topic.

Or worse.

In 2012. James Holmes shot and killed 12 people in a movie theatre in Colorado. When on trial, the 24-year old pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity; his attorney claimed he suffered from schizophrenia. Months later, 20-year old Adam Lanza shot and killed 20 children and six adults at Sandy Hook Elementary School in New Hampshire. He had reportedly struggled with obsessive-compulsive disorder and sensory integration disorder in his childhood.

Purposeful discussions about mental health are rare after violent attacks of terror. Instead, mental health becomes a scapegoat.

Expert-on-nothing Ann Coulter has written several columns explaining why she believes mental health is the determining factor in a shooting. Last December, Paul Ryan, Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, told the media that shootings are a result of “people with mental illness,” as if mental illness is a one-size-fits-all package deal, rather than a variety of symptoms and experiences.

These high-profile cases sparked conversations about mental health. Questions arose: was mental illness to blame for these tragedies?

These conversations are problematic for many reasons. They make it seem that we need to improve mental health treatments only to ensure that mentally ill people are not a threat to others. They also incorrectly create a link between mental illness and violence.

Mass killers should not be representatives of people with mental illnesses when there are thousands of innocent people struggling with their mental health. If we want to support those struggling, we cannot vilify them in the same breath.

Holmes’ and Lanza’s actions were indefensible, but by painting them as the poster boys for mental illness, we are causing more harm than good.

It’s never a bad time to talk about mental illness, no matter how inconvenient or un-newsworthy the topic may seem. And, perhaps, we can prevent incidents by talking before it’s too late.

The bottom line is – to quote just about every commercial, politician, celebrity, and news organization – that “we need to talk about mental health.” But next time we talk, let’s make sure we’re having the right conversation.