Having recently finished construction on a retrofit project to improve environmental sustainability, no one could say that Algonquin College hasn’t put in effort to adapt to the challenges of climate change.

Algonquin’s administration put $9 million and over a year of resources into upgrading their energy storage system and solar energy access around the Woodroffe campus, with construction of their solar photovoltaic project ending on Oct. 31.

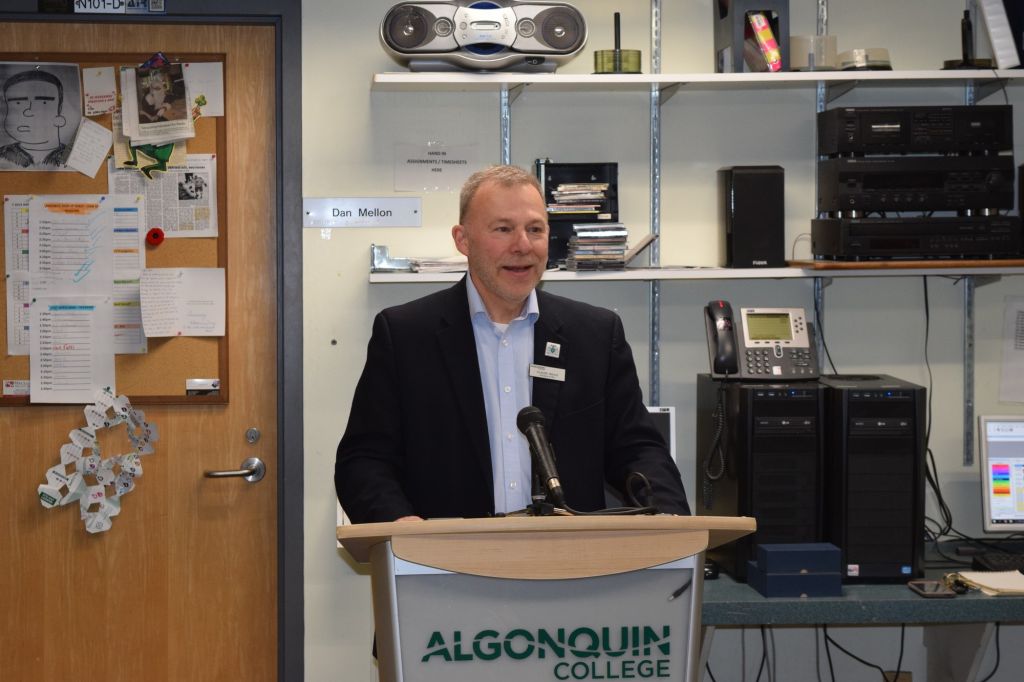

When it comes to further environmental action as well as past commitments, however, President Claude Brulé is hesitant to re-affirm or promise anything. This is especially true regarding former-president Cheryl Jensen’s 2018 commitment to Algonquin becoming a carbon-neutral campus.

“I would say we’re taking it under advisement,” Brulé said. “And we’ll react also to what different levels of government are able to signal to us and perhaps incentivize in order for us to continue down this road.”

The type of incentive that Brulé is referring to came in April 2018 in the form of a $9 million grant from the provincial government, which was the driving force in the solar photovoltaic project.

“We’ve done some projects to try to have a higher level of sustainability over time for the institution,” he said. “But, to say that it would lead us to being carbon-neutral, at this moment, the answer would be no – we’re not (carbon-neutral) right now.”

The solar photovoltaic project is one of these sustainability efforts. It is expected to provide sustainable green electricity by next year once it is fully connected to the school’s micro-grid, according to executive director of facilities management John Tattersall.

According to a McGill University paper on sustainability, “Sustainability means meeting our own needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

There are many ways to measure sustainability, and one of the tools that colleges and universities typically use to do so is the Sustainability Tracking Assessment and Rating System.

Both the University of Ottawa and Carleton University, as well as 980 other campuses worldwide, have registered their institutions with the system. Jonathan Rausseo is the campus sustainability manager at the University of Ottawa, and he is responsible for gathering all of the data and findings that go into determining the sustainability rating for a school.

Rausseo said that it would take a full-time employee approximately six months to gather all of the necessary information to register. There is also a payment required for STARS to rank the institution registering.

“Once you have collected the data, supplied all the background information, and gotten your institution’s president to officially sign off on an official letter, your report goes online,” Rausseo said.

According to Rausseo, the University of Ottawa signed up for several reasons. Showing a level of accountability and solidarity with other schools were priorities, but he noted that every school has their own reason.

Some schools have gone even further than registering with STARS, as Centennial College and the University of Toronto Scarborough are collaborating on a clean-technology venture with their new EaRTH district center.

The EaRTH district, which stands for Environment and Related Technologies Hub, will be a vertical farm that will allow students, the industry, and the community to experience what innovative technologies can accomplish sustainably.

Vertical farming is the production of food crops in vertically-stacked layers within a location. The EaRTH district will be Canada’s first net-zero energy vertical farm.