Otters hold hands in rough waters so they don’t drift apart. They are self-care advocates and they are a symbol for what is needed to do the work Farrah Khan does.

Khan, who was the keynote speaker at the FREE TO LEARN: Confronting Sexual Violence at School event on May 31, holds a masters of social work, is a public speaker on violence against women and an activist.

“It takes a community,” Khan said when she told the audience about her obsession with otters. They’re not just cute. They work together for a common goal.

Algonquin College fostered that community in the Commons Theatre with survivor stories, activists and inspirational speeches about the startling statistics of violence against women and those whose bodies are often not included in the conversation.

Khan likens the building of consent culture to science fiction.

“What we are doing as community organizers, as people envisioning different worlds, we are doing the work of science fiction,” Khan said. “We are creating new worlds that don’t exist right now.”

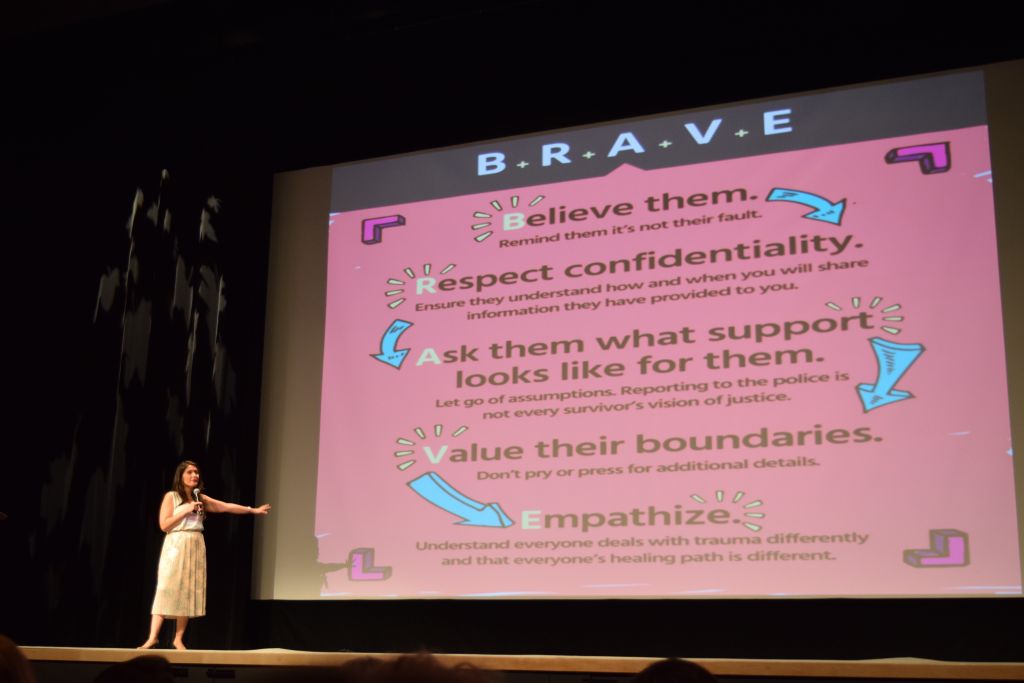

Khan also believes the first thing you need to know is how to listen. Then there are the simple things we need to say to each other, like, “I believe you,” and, “It’s not your fault”.

She grew up in a family where her mother had just barely finished high school. Her mother was the first person in her family to say no to violence.

“When I think about this work,” Khan said, “I have to ground myself. I walk in my mother’s revolution. I walk in my grandmother’s revolution. And I think about who I am following and who I am creating a better world for.”

At a mother and daughter reunion party recently, Khan said she saw a woman who asked her daughter, “What kind of ancestor are you going to be?”

The question resonated with her.

“When I think about sexual violence,” Khan said, “I think about how I want to be the ancestor creating a safe culture, creating community and worlds that are safe. And I want to be a part of communities that are creating other ancestors like that.”

She knows the work is hard. There is a scarcity of funding and an abundance of demand.

“Loving this work, thinking about this work, is radical,” said Khan.

She suggested we start by teaching children and showed a YouTube clip of queer, feminist writer and poet Staceyann Chin’s Living Room Protest III. It showed a mother and her young daughter talking about consent when it comes to picking up children without their permission. She breaks it down in a very simple way so it’s digest-able for children and those new to the subject of consent.

In Ontario, consent has only just been added to sexual education programs in schools, but there is still the responsibility for others to teach children.

“We always want to pick up kids,” Khan said, joking about how she wants to put babies’ feet in her mouth because of how cute they are. “Part of teaching consent is about teaching it to children.”

She suggests asking questions like: can I kiss you, can I hug you, to teach them that children also have choices. Consent starts early.

And consent isn’t only about sex, although the majority of conversations around consent focus on sexual activities. Sometimes even family takes away choices. Think of a mother who forces her daughter to only wear pink dresses when she wants to wear pants with trucks on them. Think about the parents who make their children study certain subjects in university that they have no interest in.

“We need to talk about pleasure,” Khan said. More importantly, we need to talk about how to communicate pleasure.

“If you can’t have conversations together about pleasure, then it is just really about conquest, commodity, or something you grab and take,” Khan said.

Because there are 460, 000 sexual assaults that take place in Canada every year, Khan believes we also need to talk about sex and violence. Especially after the high-profile case with Jian Ghomeshi, which showed that many people still conflate BDSM and sexual assault, and many people still blame victims for not reporting assaults right away or not being the stereotype of the perfect victim.

The vast majority of sexual assault cases occur with someone the victim knows and no two cases are the same.

“It’s important to understand that if it’s a friend, a family member, or a coach – if it’s someone you know – it can be harder to report,” Khan said.

And despite the myth that most claims of sexual assault are false, only two to seven per cent of cases are false – which is no more than that of any other crime,

“We need to create spaces where people don’t have to be secret keepers,” said Khan. “We have to remind survivors that their voice matters.”