With the issue of consent brought to the fore as a result of the Jian Ghomeshi trial, it’s a good time to ponder the question: what does consent really mean?

The Canadian Criminal Code’s definition of consent is pretty straightforward but can be difficult to prove in a court of law. If a person has been physically coerced, threatened, defrauded or is subject to another’s authority, consent hasn’t been obtained. And yet, many are under the impression that if a woman is intoxicated, she cannot consent.

That’s only half-true.

The law doesn’t make a distinction between men and women. No one can consent if they’re intoxicated. But, what does that mean? Is it illegal for drunk people to have sex with each other? Technically yes, but the crime needs to be reported for any charges to be laid.

Only 19 incidents were reported at the college from 2009 to 2013. This isn’t surprising since fewer than one in 10 victims report the crime to the police. Only 23 per cent of sexual assault charges in 2011 to 2013 resulted in a guilty verdict according to Statistics Canada. Than could explain the remarkably low number considering the activity that happens between students.

Algonquin has adopted Colleges Ontario’s Sexual Assault and Sexual Violence Policy which mirrors the Criminal Code and held Consent Fest last month in order to engage students on the important subject of sexual consent. Both speakers Julie Lalonde, a social justice advocate, and Laci Green, an American YouTube video-blogger and public sex educator, were invited to discuss consent, bystander-intervention, sexual assault and campus life as part of the college’s “#ItsNeverOkay” campaign.

But is this enough?

Reporting sexual assaults seems to be a bigger problem than understanding consent.

What are the reasons men assault women? Science doesn’t help answer that question.

In a study published by the European Journal of Social Psychology, a group of men and women were shown non-sexualized photographs of either a young man or young woman. After seeing each original full-body image, the participants saw two side-by-side photographs. One was the original image, while the other was the original with a slight alteration to the chest or waist. Participants had to pick which image they’d seen before.

When viewing female images, participants were better at recognizing individual parts than they were matching whole-body photographs to the originals.

The opposite was true for male images. Males were seen as a whole instead of individual parts.

Ironically, the women did exactly the same thing. Both sexes see women as objects.

This might explain why the objectification of women is so rampant in entertainment, media, video games and advertising marketed to both men and women. Are all these highly sexualized images turning men into potential criminals? It’s not likely as crime rates, including sexual assaults, have been steadily declining since 1993.

Could the gender gap be an issue? Canada’s ranking in the World Economic Forum’s annual Gender Gap Report has been dropping since it was first published in 2006. We started at number 14. We’re now number 20.

The ranking is calculated based on four factors: economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health and survival and political empowerment. Iceland currently tops the list, followed by Finland, Norway and Sweden. Sweden boasts the highest percentage of women in a European parliament. It also has one the highest sexual assault rates in the continent.

The reason is not only because of the treatment of every incident of assault as a separate case, but also because of a raised awareness and changing attitudes towards reporting them.

The overall crime rate in Nordic European countries is low, but sexual assaults are still high in comparison. Instances in Iceland usually happen between Fridays and Sundays from midnight to 9 a.m. In only 11 per cent of cases neither the perpetrators nor the victims had consumed alcohol or any other substance when the assault took place. Like many northern countries, Iceland is a country of binge drinkers, something many college students can relate to.

Should alcohol be banned from campuses?

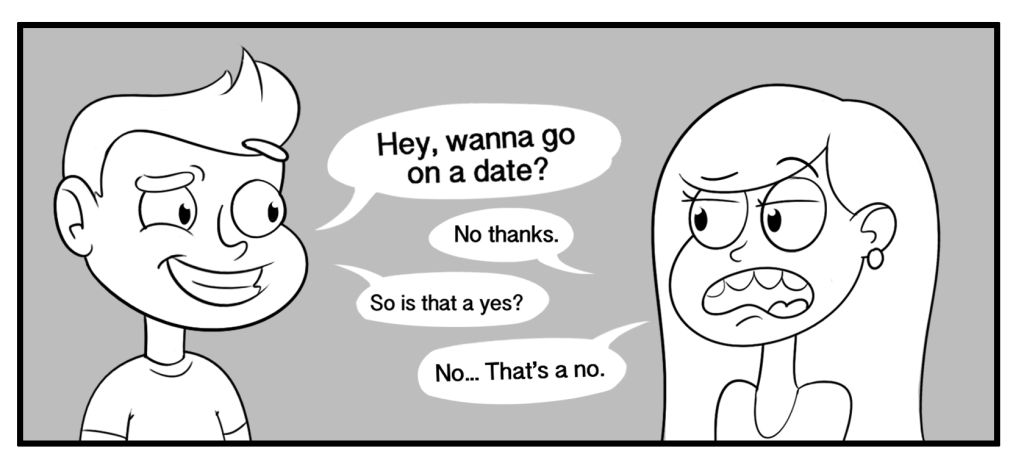

One could argue that it would help prevent assaults but this is unlikely to happen. We need to acknowledge alcohol’s effect on how it affects our own behavior and its role in sexual assaults but also challenge our own views on consent. Respecting others as well as yourself is key. Knowing your limits when you’re drinking and when you’re dealing with others is necessary in promoting a culture of consent and ending sexual assault. So, consent is not that difficult. It’s something you practice every day. It’s how you interact with others. It’s being aware of personal space. It’s being considerate. It’s making someone laugh. It turns into assault when empathy for others is lost, when both your physical and emotional senses are ignored and when you stop listening to others and your conscience.